What does it mean to have a soul? What does the word ‘soul’ mean anyway? Possibly not what we think it means…

What does it mean to have a soul? What does the word ‘soul’ mean anyway? Possibly not what we think it means…

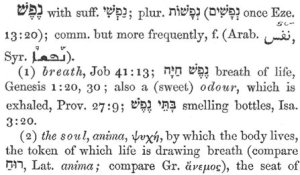

The Hebrew word usually translated ‘soul’ is nephesh נפש. Certainly in the Greek translation of the Old Testament (called the Septuagint), and in the New Testament, the word meaning ‘soul’ (psyche ψυχη) was used for nephesh. The problem with translation is that it is very easy to import an understanding of a word that isn’t there in the original. Bishop Tom Wright has been talking about this, as he thinks that is part of what has happened in this case.

Wright argues that when the New Testament use the word psyche they were using it as a translation of nephesh. And so not in the sense that Plato and others used and use it to mean ‘soul’ as separate from ‘body’. Rather, nephesh means something more like “living, breathing creature” (as Wright renders it). That’s seen in the shift away from translating it as ‘soul’, as well. So, of the 750+ occurrences of nephesh, the Septuagint used psyche 600 times, the King James Version uses ‘soul’ 475 times and the NIV (1984 version) uses the word 105 times. The NIV uses ‘life’ 129 times (117 in the KJV).

It’s also notable that it’s not exclusively used for humans. In Genesis 1 and 2 it is the word translated as ‘living creature’. All of which points towards the ‘soul’ being far more embodied than we normally think (and also raises interesting questions about the theology of animals!). But, it’s not only in theology where the importance of understanding embodiment is becoming more important.

In his book on the prehistory of human identity Origins and Revolutions (2007), Professor Clive Gamble highlights the importance of our embodied nature for understanding the world. He argues (p67) that:

Our bodies therefore structure all forms of communication and meaning and are a focus for our identities.

Gamble goes on to discuss recent studies of Artificial Intelligence, which he says have rejected the understanding of thinking as something separate, but instead turned to an approach of “being-in-the-world”. Gamble (p68) writes:

Through materiality we are both engaged with and constituted by , the world of objects, artefacts and ecofacts distributed across landscapes and in locales.

In other words, how we think, how we understand, depends on our experiences of being embodied, thinking beings. All of which should be another push towards us realising that creation, and our interaction with it, is an integral part of who we are. That this needs saying shows me that we’ve still got a way to go before we get out of the Greek mindset of ‘souls’ being separate and that we can ‘escape’ to heaven, rather than work for the new heaven and the new earth here and now.